| “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have

postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic

material.” —J.D. Watson and F.H.C. Crick |

|

Maurice Wilkins |

|

|

|

Linus Pauling |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Watson letter to

Delbruck |

|

|

|

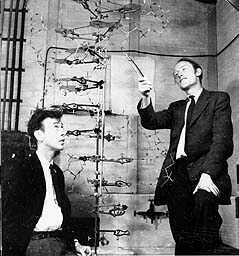

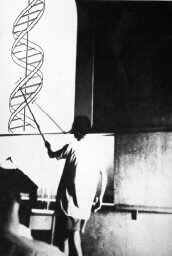

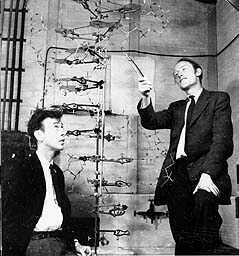

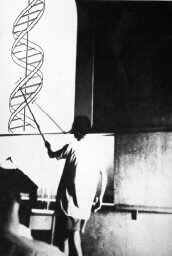

The Double Helix By the early 1950s the tools were at hand for understanding the structure of DNA. The work of Avery and Hershey had shown that the secrets of the gene lay in this molecule. Chargaff’s discovery of the ratio of the bases provided a vital clue to the arrangement of its components. Laboratories in England, California, and elsewhere were using a technique called x-ray crystallography to reveal the structure of large molecules. In 1951, James Watson (1928-) and Francis Crick (1916-) joined forces at the Cavendish Laboratories at Cambridge University. It took them only two years to solve the problem: Watson and Crick published their DNA structure in the April 25, 1953 issue of the journal Nature. "Secret of Life" The double-helix structure that Watson and Crick proposed for the DNA molecule immediately attracted attention. A crucial insight was the pairing of the bases, adenine with thymine, and guanine with cytosine. The structure suggested a way that genes could copy themselves, a process essential every time a cell divides. In effect, the double helix could unzip, each of its strands serving as a template for the formation of a new helix. As Crick put it, he and Watson had found “the secret of life.

|